Unlocked area

24.04.2025 – 24.05.2025

Solo exhibition of artist Sergio Limonta

press preview: Thursday April 24th, 2025 at 11.00AM

opening: Thursday April 24th, 2025, from 5.00PM to 8.30PM

BUILDING TERZO PIANO presents from April 24th to May 24th, 2025 Unlocked area, an exhibition that brings together a selection of six works by artist Sergio Limonta, including new works and site-specific productions created specifically for the exhibition.

The solo show is also accompanied by a critical text by Alessandro Rabottini.

In regards to his poetics, artist Sergio Limonta says, “My gaze, in reaction to the surrounding, is turned to the environment; whether this is the interior of the studio – with the materials I accumulate, the works that confront and recall each other, or the drawings of works not yet created – or the exterior, in that environmental vision that we call ‘Landscape.’” In particular, the Landscape the artist observes for inspiration is that of industry: metaphysical spaces made up of large rooms, squares, entire neighborhoods that depopulate to silence at a set hour. In addition, Limonta is focused on the aesthetics of materials and artifacts, of the marks that work imprints on the environment.

Limonta’s artistic research takes the form in the reuse of accumulated and discarded materials that are transformed into synthetic and radical works, giving new life to industrial materials.

The works on display in the exhibition correspond to the different fields of research and development in the artist’s work, collectively contributing to establish an interrelationship and harmony with the exhibition space, both in the space’s architectures and conceptually. In BUILDING TERZO PIANO, the works force the space, placing themselves on the edge of the volume; in fact, the presence of the individual work is not to be counted solely by its dimensional scale, but also by its visual “footprint,” which, in some cases, can also be determined by its light intensity.

The exhibition path opens with Graffiti (2025), the largest work among the ones on display. The installation is presented as an environmental intervention that relates to the architecture of the place: the painted metal shelves that make up the work profile a part of the central space following the walls, thus defining itself as a site-specific intervention.

At the center of the space, the work Love is in the air (2023) is placed. It is developed from simple assemblages of tubular lights and metal stands. These two elements, joined together according to the combinatory limits dictated by their own design, allow the definition of simple forms that, from time to time, relate to the architecture of the place and the context in which the intervention is developed.

The path continues with the works Toro and Power of the East, both dated 2025 and belonging to a series conceived from 2021: consisting of sturdy metal frames designed specifically for each work, the two installations house a series of LED tubular lamps. The visible nature of the metal and the cold neon light contribute to the work’s almost industrial artifact appearance.

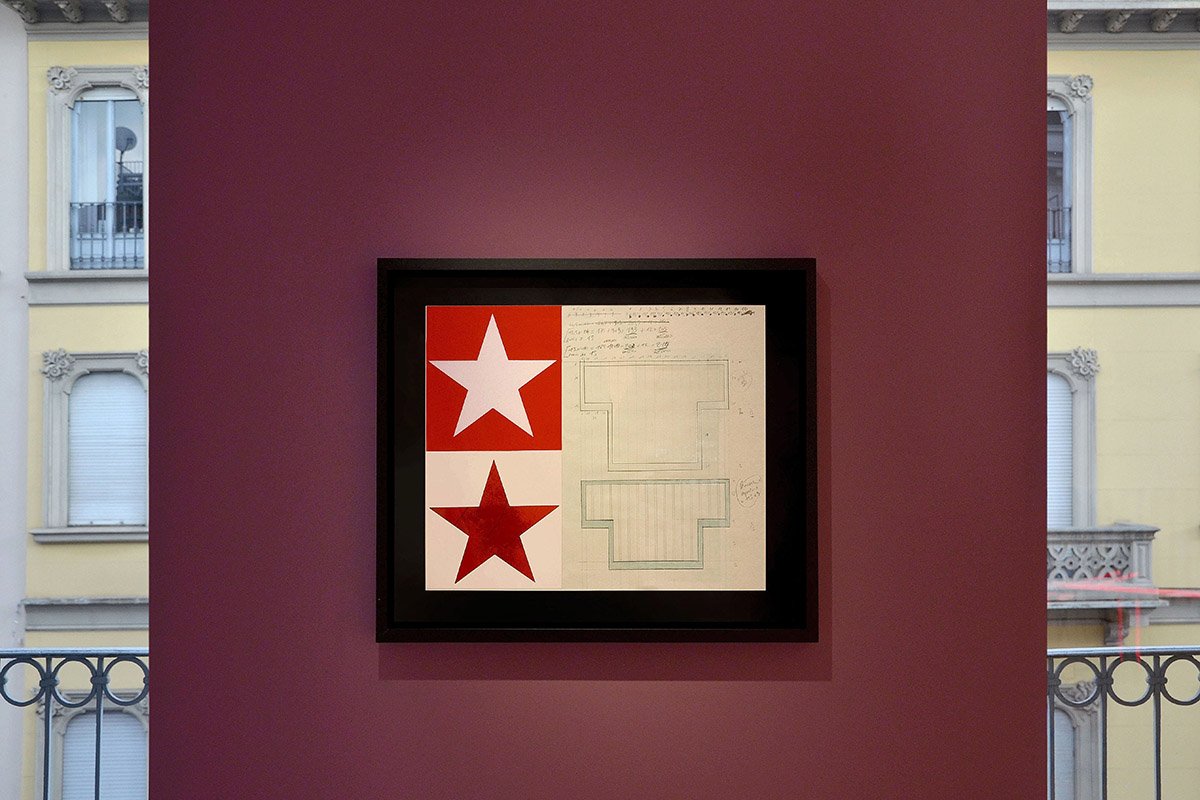

Finally, two collages made from preparatory boards, work plans, and study materials are presented.

Horizon of availability

It seems that a particular part of the world, at least that which we are fortunate enough to know and inhabit, experiences a condition of extreme and immediate availability. Things are accessible, instantaneous and prearranged, exponentially designed in favor of ever-increasing and personal needs. An expanse of manufactured goods as vast as a horizon that that one’s gaze cannot embrace, a horizon that exceeds. The constant replication of standardized measures that add up to each other, progress, become more precise by means of expansion.

With this regime of availability and immediacy of things, Sergio Limonta’s works seem to connect: spray paint, metal profiles and LED tubular lights are for the most part their materials, taken in the sizes and variations that the industry already offers.

There is a story that runs through the stories of contemporary art and ferments within it, reappearing at several points on the surface, at moments that may be distant from each other, and it is the story of the relationship between creativity and standardized materials, commercially available measures and things that are immediately available. It is a story that, beginning with Dada and through artists such as Emilio Prini, Alighiero Boetti, and Dan Flavin, has highlighted a moment in Western history by identifying it with the emergence of ever greater and easier access to things and their prefabricated manifestations. A moment in Western history in which certain materials appeared in everyday life as new, presenting themselves as the coating of a galloping modernity that seemed never to stop. And there is another story, which is intertwined with the previous one, and which sees sculptural gestures transferred elsewhere, from artists’ studios to the spaces of specialized fabrication. In this story, the material is not molded or forged but first designed and then executed by others, its are the properties of mechanical calculation and finishing. Here art absorbs into itself fabrication procedures specific to industrial design, according to a line of porosity between atelier and workshop that, beginning with the minimalism of Donald Judd, reaches to the present day through the Finish Fetish movement of Robert Irwin and John McCraken.

The materials and procedures of Sergio Limonta’s works are located in the interstices of both of these histories: while some of them have been part of the urban landscape for decades now and beyond – and seem to take the economy of the readymade for granted –others are attuned to the present technological possibilities of advanced manufacturing. Still others, with industrial production entertain an only apparent relationship of mimesis: the hues of the spray paints in Graffiti (2025), for example, are not found on the market but have been requested and produced, according to a principle of subjective variation and individual regeneration of a sign, such as that of urban graffiti, to which we are so much exposed on a daily basis, that we now consider it the object of a deaf and accustomed perception. In place, there seems to be an ambivalent tension with respect to the domain of availability and obtainability, a willingness to inhabit this domain while seeking, within it, a space of expressive autonomy. It is a tension that accommodates an impulse that is both pragmatic and poetic, such as that of seeking one’s own position in relation to what is available, how to respond to the need to do with what is around. To find an alignment with the forms of things as they are offered, as they exist, as they can be ordered and bought. This alignment becomes a field of formal elaboration, the space of a personal and temporary architecture, laid down rather than erected, ready to retreat, made almost for one body. An architecture of saturation, which seems to reach for a void by occupying space.

There is here a constructive logic that proceeds by assemblage and that of assemblage manifests all the reversibility. A logic that is not only internal to each work but also extends to the relation of each work to the others in space. Here light, like volumes, is an encumbrance, however temporary, and at the same time a temperature, a thing of touch and not only of sight. The space is occupied and defined, assembled by things and materials with which we entertain a feeling of familiarity, which we also find outside, in the world, on the street. They are, at the same time, the materials and forms of immediate availability and those of a false mimesis, and in this in-between territory we move, often not knowing how to recognize the difference, looking for it in a horizon that we cannot embrace with our gaze, within a modernity that does not stop, that exceeds.

Alessandro Rabottini